It’s an old art, ornithomancy, this reading the omens of birds. The ancient prophet looked to the sky to see what the world would become; the prophet now scries the birds to see what the world is. Tracy Zeman, in Interglacial, may well be our current poet-prophet, trekking the shore of Lake Superior, conjuring the power of the ostensive—naming the names—to work through the elements, seeking out the “atom knowledge” embedded in the world, a knowledge that allows the knower to be enfolded in the known. Old masters walk with her—Niedecker, Issa—and the voices of living poets whisper through every poem, fusing a moment’s living intimacy with time’s geologic sweep. The result is a book of nearly hypnotic beauty, lulling us awake into the sparrow-quick attention that is our earthly due.

—Dan Beach-Quick, author of Circle’s Apprentice

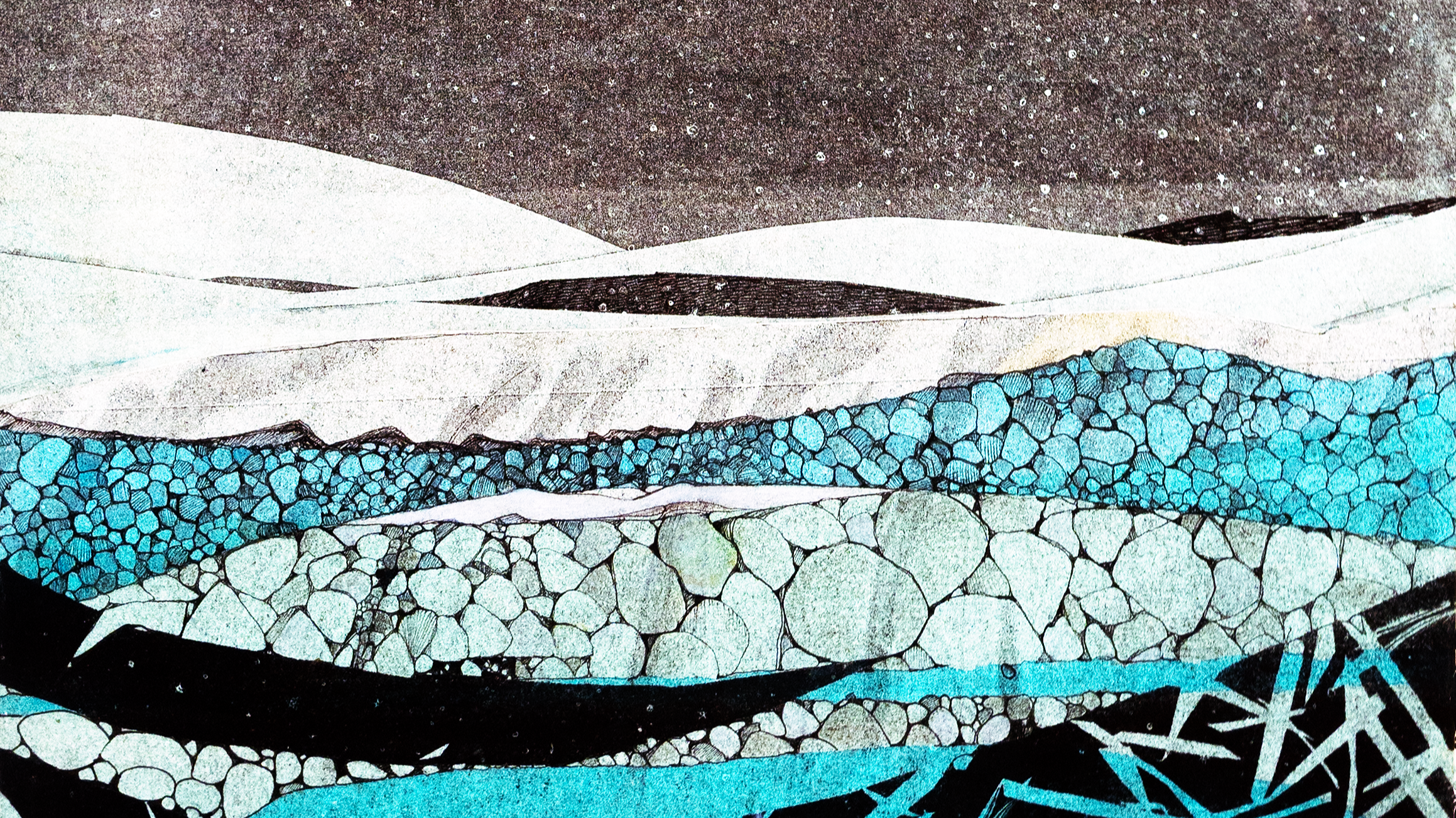

Tracy Zeman’s Interglacial invokes a “commonwealth in / sea & syllable,” rendering the coast of the Great Lakes as lines in flux, both shaping and shaped by language. No naïve pastoral, these poems border scatterings of styrofoam and Superfund Sites, reminding us that our moment is one of ecological crisis. Each of Zeman’s poems builds a layered linguistic ecosystem collaging various resources—literary, taxonomic, ecological—though Zeman’s sound is all her own. Precisely carving her lines to mimic a shoreline’s divots and gaps, the poet reminds us of the monumental forces that came before (glaciers now absent) and of the smaller impressions we leave behind, commemorated by the beach stones her “daughter” (the future’s voice) “wants to keep.”

—Kelly Hoffer, author of Fire Series

Throughout this exquisite ramble in the Great Lakes region, Zeman practices a kind of active attention, not so much observing as participating in the most minute details of a given moment, and in ways that engage all the senses. In its embrace of particulars, Interglacial pays homage to Lorine Niedecker while, formally, it also pays tribute to the haibun tradition, as we travel along with the writing eye, often brought to a stop by intense moments of concrete realization.

—Cole Swensen, author of On Walking On